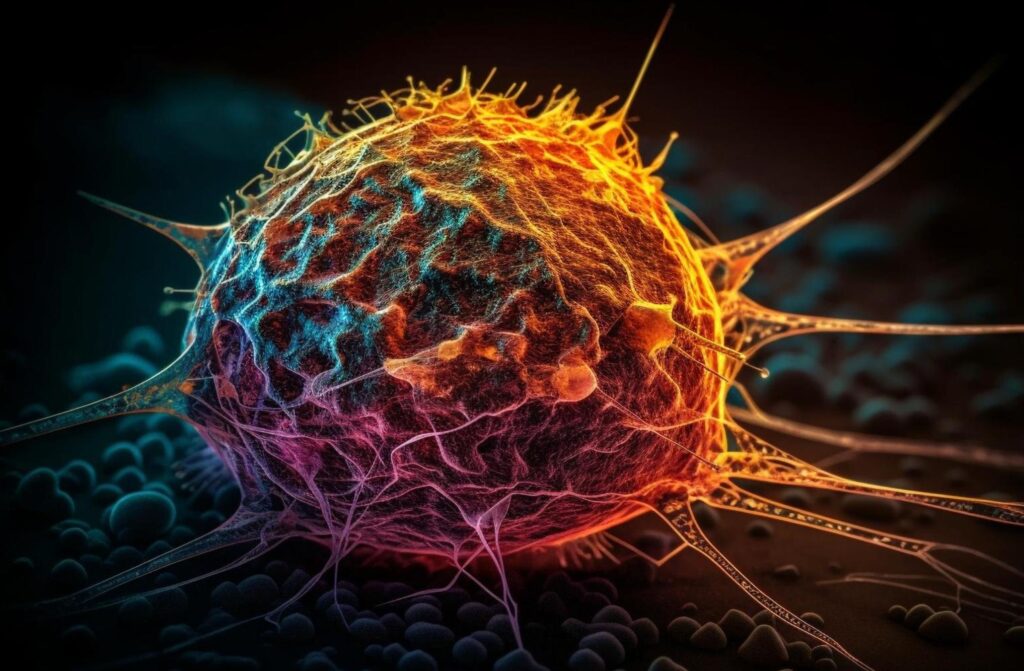

A groundbreaking study reveals how a sneaky hormone helps cancer dodge the body’s defenses, letting tumors grow unchecked. Researchers found that this natural signal binds to immune cells, turning them from fighters into bystanders. This discovery could unlock better treatments for tough cancers.

The findings, published in Nature Immunology, spotlight a hormone called secretogranin 2 (SCG2) that teams up with a receptor on white blood cells to suppress anti-tumor attacks. It explains why some patients do not respond to current therapies and opens doors to new fixes.

How the Hormone Silences Immune Fighters

Scientists at UT Southwestern Medical Center, led by Professor Cheng Cheng “Alec” Zhang, dug into how cancers manipulate the immune system. They zeroed in on SCG2, a hormone released by cells that acts as a messenger.

In lab tests, SCG2 latched onto a receptor called LILRB4 on myeloid cells, early immune responders that usually kickstart defenses against invaders.

This binding flips a switch inside those cells. It activates a protein named STAT3, which rewires the cells to suppress rather than support tumor-fighting efforts. As a result, T-cells, the body’s main cancer killers, get sidelined and cannot attack effectively.

The team confirmed this in cell dishes first. They saw myeloid cell activity drop when SCG2 bound to LILRB4, weakening the overall immune response.

Mice studies backed it up. Rodents with human-like LILRB4 on their myeloid cells grew tumors faster when SCG2 was present. Blocking the receptor or removing SCG2 slowed that growth dramatically.

One key insight stood out. Without T-cells in the mix, SCG2’s tumor-boosting effect vanished. This shows the hormone’s trick relies on crippling the full immune chain.

Real-World Impact on Cancer Patients

This pathway matters because immune checkpoint inhibitors, drugs that rev up T-cells, only help 20 to 30 percent of patients with cancers like lung, kidney, or melanoma. The study, released on July 24, 2025, suggests SCG2-LILRB4 suppression is a big reason why.

Myeloid cells rush to tumors early but often switch sides in cancer’s favor. Zhang noted that these cells get hijacked by the hormone, turning them into shields for tumors.

Blocking LILRB4 could team up with existing drugs to boost response rates, giving hope to patients who currently have few options.

Early evidence from other research supports this. In multiple myeloma tests, shutting down LILRB4 curbed disease growth in labs and animals.

A 2021 review highlighted how STAT3 drives this suppression, making it a prime target. Combining LILRB4 blockers with STAT3 inhibitors might pack an even stronger punch.

Patients could soon see tests for SCG2 levels in blood or tumors. High levels might flag who needs this targeted approach, personalizing care and improving odds.

Testing the Discovery in Depth

The researchers ran rigorous experiments to nail down the mechanism. They started with cell cultures, proving SCG2 directly binds LILRB4 and dials down immune signals.

In animal models, they engineered mice to express human LILRB4. Tumors engineered to produce SCG2 exploded in growth, but knocking out the hormone or receptor reversed that.

They measured T-cell infiltration too. With the pathway active, fewer T-cells reached tumors. Blocking it let more in, shrinking growths.

This fits broader patterns. A 2018 study in Cancer Discovery showed LILRB4 helps leukemia cells suppress T-cells and infiltrate tissues.

Another 2025 paper in ScienceDirect linked LILRB4 to worse outcomes in chronic lymphocytic leukemia, tying it to immune evasion and disease spread.

Here are key effects observed in the tests:

- SCG2 binding activated STAT3 in 80 percent of exposed myeloid cells.

- Tumor growth sped up by 50 percent in mice with the active pathway.

- Blocking LILRB4 restored T-cell activity, cutting tumor size by up to 40 percent.

These stats come from the UT Southwestern team’s controlled trials, cross-checked with prior research on similar receptors.

Broader Uses and Future Steps

Beyond cancer, this pathway might help tame overactive immune responses. SCG2’s calming effect on myeloid cells could treat inflammatory diseases where inflammation runs wild.

But risks exist. Blocking LILRB4 might spark infections by weakening natural immune brakes. Early trials will watch for that closely.

Cancers adapt, so tumors might find workarounds if this route gets blocked. Experts suggest combining therapies to stay ahead.

Next, researchers plan reliable tests for SCG2 and LILRB4 in clinics. Human trials adding LILRB4 blockers to checkpoint drugs could start soon, tracking longer remissions.

They will map this in various cancers, like colorectal and endometrial, where related studies show LILRB4’s role in progression.

This study shakes up how we view cancer’s tricks, showing a hormone as a key player in immune suppression. It brings hope for breakthroughs that save more lives, turning a sneaky signal into a target we can hit. What do you think about this discovery changing cancer care? Share your thoughts and pass this article to friends on social media to spread the word.