China has officially rolled out a nationwide online identification system that critics warn could smother digital privacy and intensify repression. While authorities say it’ll make the internet safer and more convenient, human rights groups are calling it a big leap into total digital surveillance.

Coming into effect Tuesday, the new online ID rule requires users to link their national ID cards and facial data to a government-backed authentication app. The move is voluntary — for now. But with major platforms like WeChat already adopting it, experts say it may not stay that way for long.

Surveillance With a Friendly Face

On paper, the new mechanism looks harmless — even helpful. According to China’s Cyberspace Administration, the system is designed to “protect citizens’ identity information and support the healthy and orderly development of the digital economy.”

Once registered, users receive a unique “internet code” and digital “internet certificate” that allows them to log into apps and services more easily, skipping passwords and repeated form-filling.

Sounds like convenience, right? Until you realize what’s beneath the surface.

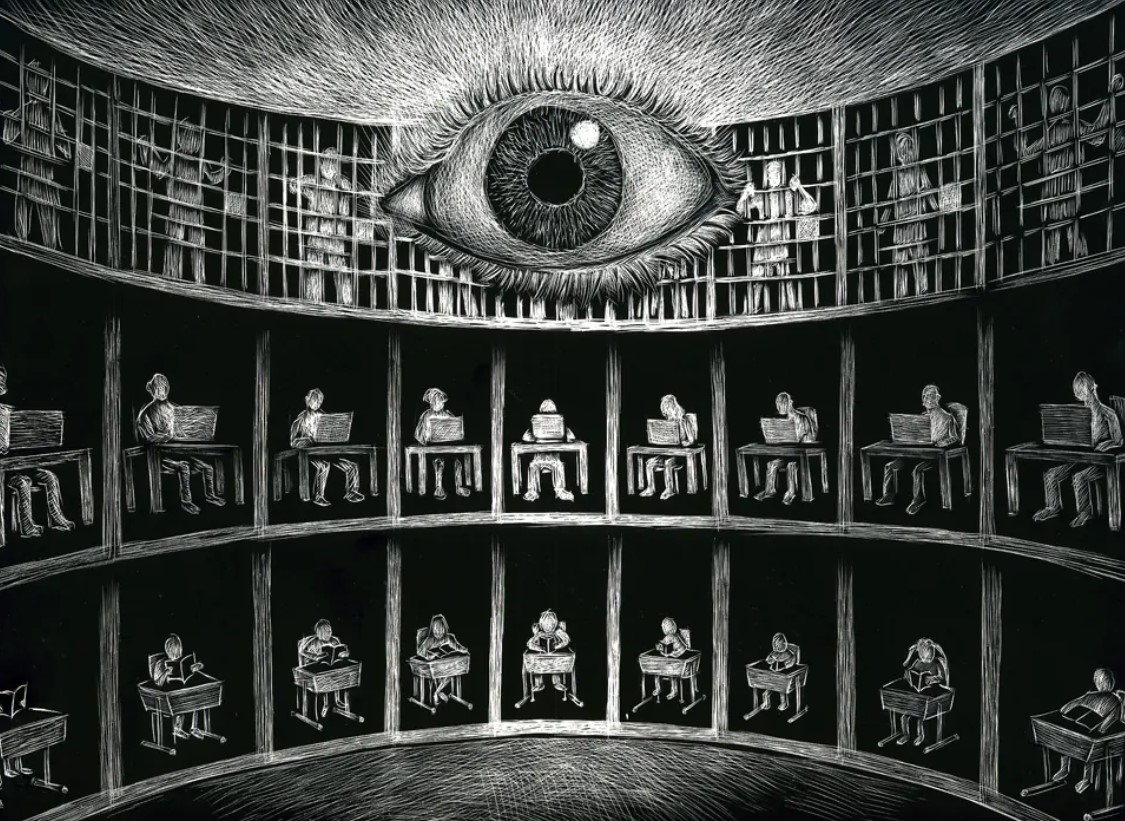

Behind that shiny tech is a state tracking system that watchdogs say could dramatically shrink what little room is left for online dissent. With the state now having deeper access to the digital footprints of over a billion users, anonymity is vanishing — fast.

Why Rights Groups Are Sounding the Alarm

To be clear, China’s internet hasn’t been free for a long time. Between the “Great Firewall” and the 2017 Cybersecurity Law that already demands real-name registration, there’s little breathing room online.

But rights groups say this new move takes things to an entirely new level.

Shane Yi, a researcher with Chinese Human Rights Defenders, called it “a dangerous escalation.” His group warned last month that this is just the latest tool in a broad, systematic effort to silence dissent.

Xiao Qiang, an internet freedom researcher at UC Berkeley, put it even more bluntly: “It’s not just surveillance. It’s digital totalitarianism.”

Here’s What the System Actually Does

The idea is straightforward: tie every internet activity back to a traceable, government-verified ID. But what it means in practice is more complicated — and worrying.

For starters, the app requires users to verify themselves using:

National ID card numbers

Facial recognition scans

Phone numbers already linked to their real names

Once verified, users get a permanent internet identity code. This replaces traditional login processes on participating platforms — skipping passwords and letting people log in with their digital ID.

But this also means that every click, post, or payment can be tied directly back to the individual — with no possibility of hiding behind a screen name.

A Dangerous Future for Free Speech

In a country where even mildly critical posts can lead to arrest, losing the ability to stay anonymous is more than inconvenient — it’s terrifying.

Michael Caster of free-speech group Article 19 warns that stripping away online anonymity is a direct threat to the “freedom of opinion and expression.”

China’s system, he says, will likely be used to track, target, and shut down dissent before it even takes root.

And it’s not just activists or journalists in danger. Anyone — a student, a retiree, a worker — who posts something Beijing doesn’t like could be flagged, questioned, or worse.

Internet Use in China: What’s Already Required?

To understand how heavy this new system feels, you’ve got to see what’s already in place:

| Requirement | Status Since | What It Means |

|---|---|---|

| Real-name SIM card registration | 2013 | No mobile service without linking ID |

| Real-name social media accounts | 2017 (Cyber Law) | Platforms must store identity-linked activity |

| VPN restrictions | Ongoing | Only state-approved VPNs are legal |

| Content censorship & filtering | Since early 2000s | AI + human moderators erase “sensitive” posts |

Voluntary… Until It Isn’t

Right now, signing up for the ID system isn’t mandatory. But the writing’s on the wall. Officials are “encouraging” adoption by service providers and users. Popular apps like WeChat and Alipay are already on board. Smaller apps may soon follow or be forced to.

And while authorities claim it’s optional, the practical reality might look different. Without it, users could soon find themselves locked out of key services — from banking and job boards to government portals.

That’s not choice. That’s coercion in slow motion.

Official Line vs. Global Backlash

Beijing insists this is about public safety and digital economic growth. An unnamed Public Security Ministry official told Xinhua that it “ensures secure and convenient identity verification for citizens.”

But abroad, the move is drawing heavy criticism. Advocacy groups and privacy experts say it’s the latest phase in China’s mission to build a digitally obedient society — where the cost of speaking up is simply too high.

They also fear other governments may try to copy China’s model under the guise of “national security.” Already, some authoritarian states have shown interest in similar tech.

Michael Caster says it best: “In chipping away at what little online anonymity remains, China is sending a chilling message — not just to its people, but to the world.”